Tell You What: My Blog

April 27, 2023

By Rob Shapard

Could Georgia really get a national park and preserve in 2023, the first in the state’s history? It is an audacious dream for sure; but advocates have made impressive progress in recent years.

And from what I have learned so far in reading and talking with folks, the park and preserve seems to me like a powerful idea whose time is about to arrive (to paraphrase a gem of truth from French wise-guy Victor Hugo). Congress and the National Park Service have taken several key steps, and advocates are hopeful for good news this year from the deciders in D.C.

The idea is grounded geographically in the Ocmulgee Mounds in Macon, Ga., and a stretch of the Ocmulgee River; and conceptually in the ecologies and human histories connected to the river.

In the go-big-or-go-home version, the park and preserve could comprise some 70,000 acres, including the mounds in Macon and the river corridor between Macon and Hawkinsville downstream (see this map of the river).

In this post, I share a few aspects of the park and preserve, as a first step in my learning and writing more about it. I see a lot to like about this possibility, from preserving ecosystems and artifacts of human histories, to creating more ways for people to interact with the land and river. And the idea is exciting to me in part because I grew up about fifty miles from Macon and thrived largely on two things: getting outdoors to explore forests, fields, lakes, and streams; and learning the histories of middle Georgia and the American South.

So, what are we waiting for?

For now, we are waiting for the National Park Service (NPS) to release its “Special Resource Study” of the river between Macon and Hawkinsville. Based on this three-year study, NPS and the Department of the Interior next must state their position on whether the river corridor has what it takes to possibly become a unit of the national park system.

A draft of the study is done, and NPS and Interior officials are reviewing the draft, according to NPS staff member Chuck Lawson, whom I asked for an update recently. When ready, officials will submit the study to Congress, and release it publicly on the NPS project website, Lawson stated.

Then we wait for word from Congress.

Local leader Seth Clark told me this week that he remains very optimistic Congress will take action this year in favor of the park and preserve. Clark is executive director of the community-based Ocmulgee Mounds National Park & Preserve Initiative, and an elected official in the Macon-Bibb County government.

He pointed out that Rep. Sanford Bishop, a Democrat, and Rep. Austin Scott, a Republican, both have consistently supported the project, a sign of the strong bipartisan support that has held for many years. The park and preserve would be within the congressional districts represented by Bishop and Scott, and Scott’s office is drafting a bill for the House (Democratic Sen. Jon Ossoff is doing the same in the Senate), Clark said.

Seeing people work so well together in a broad coalition has been a major highlight for Clark, who grew up near Macon and has spent a lot of time fishing and hunting along the Ocmulgee.

“It is refreshing to know that we’ve still got that in us as people, that when it comes to taking care of a place you love, people will check their party identity or their one-issue identity at the door and work together,” he told me. “I’m proud of this community, and it is really special to be a part of it.”

How did we get to this point?

To reach the present moment, a whole bunch of stuff has happened since the 1930s related to the mounds and river. Here are a few specific milestones:

1936 – Congress and Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Ocmulgee Mounds National Monument, preserving about 700 acres that included the mounds and surrounding land. Actually, local and state leaders at that time were pushing for a new national park there to include some 2,000 acres, but FDR ultimately took the national monument route.

Since then, archaeologists have recovered more than three million artifacts at the monument property, and many thousands of Georgia school kids and other visitors have walked the grounds, climbed the mounds, and learned some of the history.

2009 – To pursue a vision that had been percolating for many years, local advocates established the Ocmulgee National Park & Preserve Initiative in Macon. The initiative has been persistent, creative, and skillful.

2019 – Congress passed the Dingell Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, which addressed many projects around the country. The great news for the park and preserve was that the law authorized the Special Resource Study for the Ocmulgee corridor.

Green-lighting the study was a big deal; it meant the park and preserve idea was gaining serious traction, even though there was no guarantee (and there still is not) it would become a reality.

The 2019 law also gave NPS authority to expand the preserved area around the mounds to 3,000 acres; and the law redesignated the site as the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park.

2022 – As major steps in the expansion, partners worked with NPS to acquire nearly 1,000 acres adjacent to the mounds and river; and the Macon-Bibb County government donated an additional 250 acres to NPS.

These new additions are within the area known as the “Ocmulgee Old Fields” or “Macon Reserve.” The Old Fields/Reserve include lands “specifically retained by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation from 1805 until the 1826 Treaty of Washington, which in addition to other treaties culminated in removing the Muskogean people from their ancestral home to present-day Oklahoma,” according to NPS.

“This additional property includes some of our most important unprotected ancestral lands,” said Muscogee principal chief David W. Hill in an NPS statement.

“The Muscogee (Creek) Nation has a long-standing history of preserving the Ocmulgee Old Fields-Macon Reserve,” Hill said. “We have never forgotten where we came from and the lands around the Ocmulgee River will always and forever be our ancestral homeland, a place we consider sacred and a place with rich cultural history.”

Building a broad consensus

I talked recently about the mounds and river with Dr. Robbie Ethridge, who was born in Macon and now is professor emerita of anthropology at the University of Mississippi.

She has been studying and teaching about Indians in the American South for decades, and she served on an advisory board for NPS about native histories in the Ocmulgee corridor. Ethridge has a deep affinity for Georgia, and she loves the park and preserve idea for several reasons.

“If you read my work, I’m all about rivers,” she told me. “I just love the idea of [focusing on] a portion of a river. It captures the river; it captures the history of that river. It captures the ecology of the area, much of the history of the area. For the public, it really can open up new ways of thinking about the past, and new ways of thinking about our natural resources and the natural beauty of a river corridor.

“Also, as a fan of parks and going to parks, the idea of having bike trails and walking trails that go more than just around in a circle for a mile or two, that you can actually get your teeth into, right in the middle of Georgia, I really like that idea,” she added.

To me, the progress of the park and preserve toward federal approval is remarkable, even miraculous, when I think about the powerful, relentless drive in Georgia to develop land and other natural resources for profit, often at the expense of natural ecosystems (not to say that drive is only a Georgia thing).

So, the strong support for an Ocmulgee park and preserve says a lot to me about the dedication of people who have been working for this vision, from within and beyond the local community.

The support also reflects a larger context, in which people and organizations have fought for decades across Georgia and the South to protect ecosystems, wildlife, water, plants, trees, and beautiful places. They have built an influential voice for conservationist ideals.

The goal is a national park and preserve because this would allow hunting and fishing along the river to continue; it also would allow extraction of resources such as timber and clay in some areas. The exact balance between allowing such uses and limiting what people could do within the park and preserve probably will be addressed in the legislation.

Many questions will remain important, such as what impacts activities like timbering and clay-mining might have on the land and river; and for folks who hunt and fish along the river, whether the level of access will be enough for their interests. The state of Georgia is a key player here, since the state controls the Oaky Woods, Ocmulgee, and Echeconnee wildlife management areas (WMAs) within the river corridor.

But advocates recognize clearly that the ability to hunt, fish, and possibly cut timber or mine clay in certain areas is important to some of the stakeholders; and seeking a park and preserve therefore has been essential for building a broad consensus.

Along these lines, the intent is that a law establishing the park and preserve will protect the rights of private landowners within the boundaries, according to Clark. Supporters are calling for no use of eminent domain by the federal government to acquire land; this would mean NPS could work only with willing sellers, Clark said.

“That is a really important aspect,” he told me. “There will still be private ownership in a park and preserve. The legislation will protect the property rights of owners within the boundary, so if you have land and don’t want to sell, that right will be protected.”

The goal is to get this land into conservation, and there are many ways of doing that well, Clark said. Landowners and groups such as hunting clubs already are providing valuable conservation for thousands of acres, as does the state Department of Natural Resources through the WMAs along the river, he added.

As an important advocate, the Georgia Conservancy has stated that it shares the vision for the park and preserve “in which a mosaic of lands, some publicly accessible and some with private rights retained, are managed in a coordinated manner that emphasizes conservation, recreation, cultural recognition, and ecological restoration. Central to this vision would be continued permission for hunting and fishing, along with working lands (agriculture and forestry).”

In my view, this model does have a great deal of appeal, even though pulling it off figures to be challenging. Wrestling with the devil in the details surely will take boatloads of communication in good faith, smarts, wisdom, and patience (probably already has).

Why all the fuss about the Ocmulgee?

Reporter Chris Dixon from the Washington Post explored a few spots in the Ocmulgee corridor with local advocates last year. As Dixon described some features of the river’s ecology, “The floodplain is home to a small, unique population of black bears. Rare Indian olive, carnivorous pitcher plants and fly traps take root here, while more than 200 species of birds such as warblers, wood storks, bald eagles and snowy egrets soar through the trees. Increasingly rare river cane, a sacred building material to the Muscogee (Creek), grows along the riverbanks, while sturgeon, shad, herring, and striped and shoal bass ply its water.”

The park and preserve would be a whole new level of commitment to valuing the flora, fauna, and waters of the Ocmulgee ecosystem; the human stories that unfolded and inscribed traces on these landscapes over millennia; and the many ways in which people draw meaning and life-energy from the mounds and river today.

For example, as mentioned earlier, citizens of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma hold the mounds and river sacred as central in their ancestral homelands. They are descended from the people who built a complex culture of mounds and farming villages along this part of the Ocmulgee beginning around 900 CE; and from native people who came before.

The park and preserve would mean greater protection under federal law for the ecologies and histories along the river, including stories from the past yet to be told, held in more than 800 archaeological sites that have not been fully studied.

It would create new means of access for people to immerse themselves in the place, to be inspired or enlightened, to get moving outside and de-stress, to notice things like sedimentation in the river and wonder about its causes, to renew their connections with the rest of nature.

The potential for connectivity is exciting as well, in my view. New trails in the park could link with existing trails in the Macon area, and with potential future trails beyond Macon and the river, such as an envisioned trail between Macon and Milledgeville, Ga. (still a dream but people are working now to build support).

Writer Stephanie Vermillion described the potential trail connectivity in 2021, noting, “Another trail that’s already underway – and growing – is the Ocmulgee Heritage Trail. The 12-mile bicycle and pedestrian path links Macon’s historic attractions, including Ocmulgee Mounds park and the Otis Redding Bridge, named for the musical icon who grew up in the area.

“In the future,” Vermillion wrote, “the route could connect to a larger central Georgia plan to transform an abandoned railway into a 33-mile bike trail connecting Macon [and] Milledgeville, creating dozens of trail miles throughout central Georgia—all linked with Ocmulgee Mounds.”

Now, you might not be inclined to walk or bike the thirty-three miles between those two mid-Georgia cities, especially in summer humidity that cooks you like a dumpling in a bamboo steamer.

Fair enough. But there also are a lot of people who would be very much into such a trail.

Where do the Muscogee (Creek) people fit in the vision?

Another type of connection is the feeling that citizens of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation hold today for the Ocmulgee mounds, land, and river. Their connection is essential to the park and preserve vision. The Muscogee nation is a lead partner in the work so far, and likely will be a leader in shaping the park and preserve if it comes to pass.

The nation’s former principal chief, James Floyd, talked with Georgia writer Janisse Ray about the mounds and river. “When I go there, I like to get out of the car,” Floyd said. “I breathe the place in. I look at the sky. I let it all wash over me, I take it all in.”

In this place, Floyd said, he thinks, “This is who we are, and we have to do all we can do to preserve it. Because it will be useful to us in the future.” The ability to go there and feel the place physically is deeply meaningful, Floyd told Ray for her essay about the park and preserve (David W. Hill is the current principal chief).

I have a true beginner’s understanding of the stories of the Muscogee (Creek) Indians, and the people who lived in this part of the world before the Muscogees formed as a nation. Their stories are fascinating, complex, and still being revealed by the Muscogee people, archaeologists, anthropologists, historians, artists, and others who seek to understand this deep past.

For me, it helps to start in the place and time of the people who built the Ocmulgee Mounds, and look backward and forward in time from there. I am drawing on the sources at the end of this post, and on expertise shared with me by Dr. Robbie Ethridge.

My understanding consists of broad strokes – as broad as the Ocmulgee in January floods. But here goes:

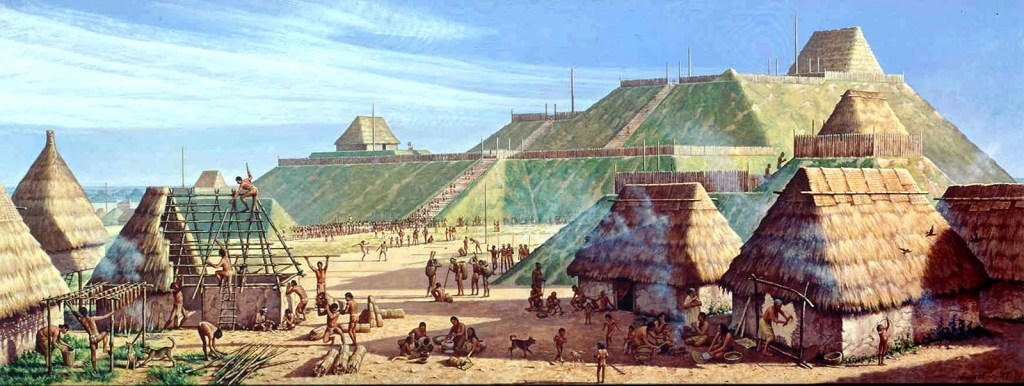

People began to build mounds along the Ocmulgee in ca. 900 CE, or about 1,120 years ago. This was during the Mississippi Period, when native people near present-day St. Louis built the city known today as Cahokia. This city was a complex of mounds, plazas, and thousands of people supported by extensive agriculture.

Cahokia’s influence spread throughout the American South and local people began to reshape their ways of life with Cahokia as a model. Some Mississippian people also migrated into areas and established new towns, which apparently is the case for the Ocmulgee Mounds.

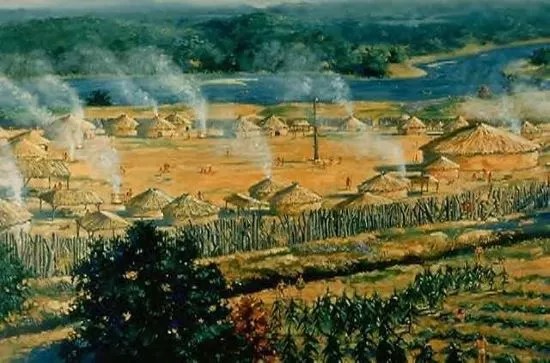

People lived within the Ocmulgee mound culture for more than 300 years; they used the mounds for ceremonies and gatherings, while leaders and other elites lived within the complex of seven mounds and held council meetings. Scholars describe this as a well-integrated chiefdom, with the mounds as the capital town and small towns along the river where people raised food in the bottomland soils, while also hunting and fishing.

What came before this chiefdom? We can wind the film all the way back to the first human presence in parts of the modern-day American South.

People first reached southern regions roughly 15,000 years ago in the last part of the Ice Age. At the southern coasts and inland, people in this Paleoindian Period hunted megafauna and smaller animals, fished, and foraged. Within an area touching on the Ocmulgee and Oconee rivers, the archaeological record shows people there at least 12,000 years ago.

As the Ice Age ended and the megafauna went extinct, people on this continent continued to hunt smaller animals and forage for food in what scholars call the Archaic Period.

And with the climate continuing to warm, people began shifting toward societies with agriculture that were less nomadic. During this Woodland Period (ca. 1,000 BCE to 900 CE), people lived along the Ocmulgee and grew crops there; and from Woodland culture, people shifted to the Mississippian ways of life, as described above.

Going into the late 1300s, the chiefdom at the Ocmulgee River and other large southern chiefdoms declined, and smaller chiefdoms developed. Along the Ocmulgee, people organized themselves into a smaller chiefdom downstream from the first mounds. For their new chiefdom, people built a capital town mounds and farmed the floodplains of the river.

More major changes came when the Spanish ventured into the southern interior in the 1500s at the start of European colonization. Over the next hundred years, Native people engaged in trade with the French and English, trading Indian slaves for guns, ammunition, and other European-made goods. Increased warfare between Indian tribes and alliances was one of the consequences of this commercial trade in Indian slaves.

Disease also swept the South and killed many Indian people. This led to the dissolution of the Mississippi Period chiefdoms, and emergence of “coalescent societies,” in which Indian people came together from disparate places and cultures.

Many of the surviving native people along the Ocmulgee, for example, migrated westward and established towns in parts of the Chattahoochee, Tallapoosa, and Coosa river valleys; they joined with others there to establish an alliance later known as the Creek (Muscogee) Confederacy.

By the late 1600s, trade with British traders from the Carolina colony was flourishing. At the Ocmulgee mounds, the British built a post in 1690 to facilitate this trade with Indians who had migrated back there from the three river valleys to the west.

During this time, the Ocmulgee River was known as Ochese Creek, and the British called the people with whom they traded the “Indians living on Ochese Creek,” or the “Creeks.” They later began referring to all the Indians westward to the towns in the three river valleys as the Creeks.

But the Creeks in fact were a confederacy of diverse peoples who spoke several different languages, such as Muscogee, Hitchiti, and Alabama.

Most Creeks moved westward again to the river towns after 1715. However, they still claimed all their lands reaching to the Ocmulgee). Meanwhile, the hunger for land in Georgia and Alabama intensified, and in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the state and federal governments forced the Creeks to cede millions of acres. In 1836-37, federal troops and state militias forcefully deported some 21,000 Creeks to the Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma).

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation is based today in Ocmulgee, Ok., and many of its citizens look to the Ocmulgee as the center of their ancestral homelands. “This land is incredibly important to the Nation, and we want to make sure that it’ll always be protected,” said Tracie Revis, in a recent interview with AFAR magazine. Revis is a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and she works as director of advocacy for the park and preserve initiative.

“It would be a significant increase in presence in their ancestral homelands,” added Seth Clark, also speaking to AFAR. “Our city’s identity is deeply defined by the act of (Indian) removal.” “We exist here because they don’t. I think it would mean a lot to both sides to have a partnership in managing this land that we each love so dearly.”

The park and preserve work has been deeply meaningful to Clark, who said in an earlier interview with the Florida Times-Union, “There’s a healing I didn’t understand needed to happen until I started working with the [Muscogee nation].

“The act of conserving this land with the stewards of now – people like my family – and the stewards who were forcibly removed, there’s an act of atonement in that process that this community is very much in need of,” he said.

Don’t you need geysers or grizzly bears to have a national park?

While Florida has three national parks (Everglades, Biscayne, and Dry Tortugas), and South Carolina has one (Congaree), there are no national parks yet in the other Deep South states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

Yes, many lame jokes are possible here, e.g. how about a Tornado Alley National Park, or Bryant-Denny Stadium NP, or Endless Pine Plantations NP? Or worse. Hah hah.

But seriously, Janisee Ray makes an excellent point in her essay that national parks do not necessarily have to blow us away with spectacular mountains, canyons, cliffs, ancient trees, geysers, or waterfalls.

She writes, “Is the South any less beautiful, less ecologically complicated, less rare, less awe-inspiring than the West? Do we need the loudness of geology to understand power? Can we have a quiet geography? Can we understand the quiet muscle of botanics?” (these, of course, are rhetorical questions; the answers are no, no, yes, and yes).

What does it take to realize such a dream?

It takes “time, labor, money, communication, creativity, flexibility, and compromise,” Ray observes. “More than anything, it takes community. How much, of course, depends on the scope and profundity of the dream. The people of central Georgia have taken on a big dream, and since it’s a national park, all of us are part of its community.”

Most people have experienced the creative power of their imaginations in their lives; Ray urges people to bring that creative power to bear in support of the park and preserve.

“If we imagine it, we create it,” she writes. “The more of us who imagine it, the easier the creation will be.”

I guess that could sound a bit hippy-dippy or trippy to some folks. But I’ll tell you what, she’s not wrong.

Sources

Bailey Berg, “The U.S. could be getting a new national park. Here’s where.” AFAR, Apr. 18, 2023 (article).

Chris Dixon, “Muscogee (Creek) Nation, conservationists seeking to establish first national park and preserve in Georgia,” Washington Post, Feb. 12, 2022 (article).

Robbie Ethridge, discussions and correspondence with the author, ongoing.

Robbie Ethridge, Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World (University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

Caroline Eubanks, “Could this become Georgia’s first national park?” National Geographic, Mar. 3, 2023 (article).

Georgia Public Broadcasting, “The Mounds at Ocmulgee: A Virtual Exploration of Mississippian Indian Culture in Georgia” (website).

Steven C. Hahn, “Creeks in Alabama,” Encyclopedia of Alabama (article).

Emily Jones, “Georgia has big conservation goals, and the military is helping to achieve them,” WABE, Apr. 18, 2023 (article).

Melanie D.G. Kaplan, “Protecting the Homeland,” National Parks Conservation Association, 2021 (article).

National Park Service, “Acquisition more than doubles the size of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park,” Feb. 9, 2022 (press release).

NPS, “Macon-Bibb County land donation adds 250 acres to Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park,” Sept. 21, 2022 (press release).

NPS, “Ocmulgee National Historical Park: Celebrating Archeology” (website).

NPS, “Ocmulgee River Corridor SRS” (website).

NPS, “The Muscogee Nation,” Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park (website).

Ocmulgee National Park and Preserve Initiative (website).

PBS LearningMedia, “Indian Mounds: Ocmulgee” (website).

Janisse Ray, “For all who have gone and all to come: Getting a national park in central Georgia,” The Bitter Southerner, Mar. 18, 2021 (article).

Claudio Saunt, “Creek Indians,” New Georgia Encyclopedia (article).

Aaron Spray, “Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park May Be The Next National Park, Here’s What To See There,” The Travel, June 28, 2023 (article).

The Georgia Conservancy, “Ocmulgee National Park & Preserve Initiative” (website).

John Trussell, “Officials seek hunting protections in Ocmulgee National Park proposal,” Georgia Outdoor News, Mar. 2, 2022 (article).

Stephanie Vermillion, “Georgia’s Ocmulgee Mounds may be America’s next national park,” Conde Nast Traveler, Sept. 22, 2021 (article).

Michael Warren, “The Muscogee get their say in national park plan for Georgia,” Associated Press, Sept. 21, 2022 (article).

Mark Woods, “An old park in the middle of Georgia worthy of becoming new national park,” Florida Times-Union, Aug. 26, 2022 (article).